“We compose our music not as a series of notes or even sounds, but as a structured series of emotional electronic experiences.”

Louis and Bebe Barron, 1955

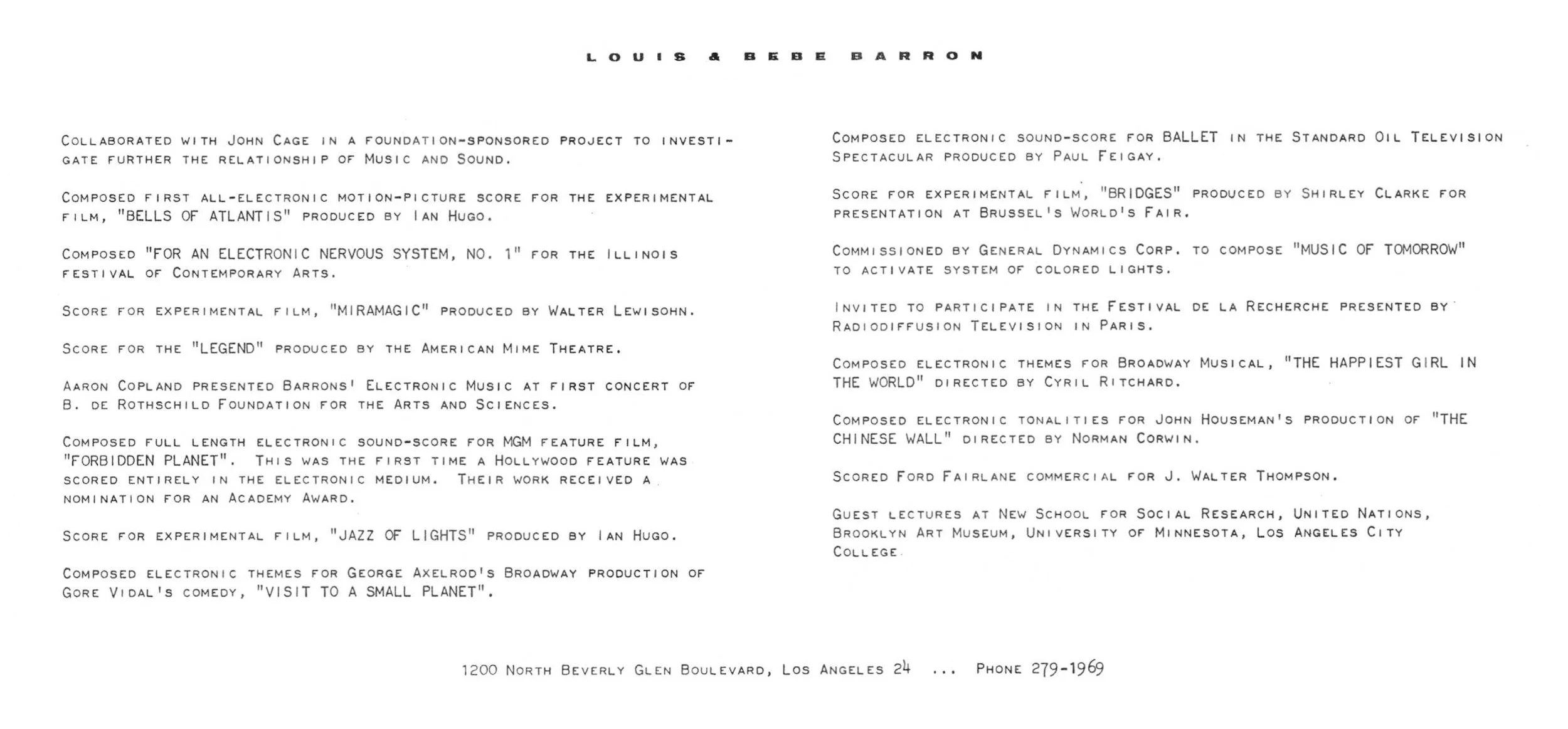

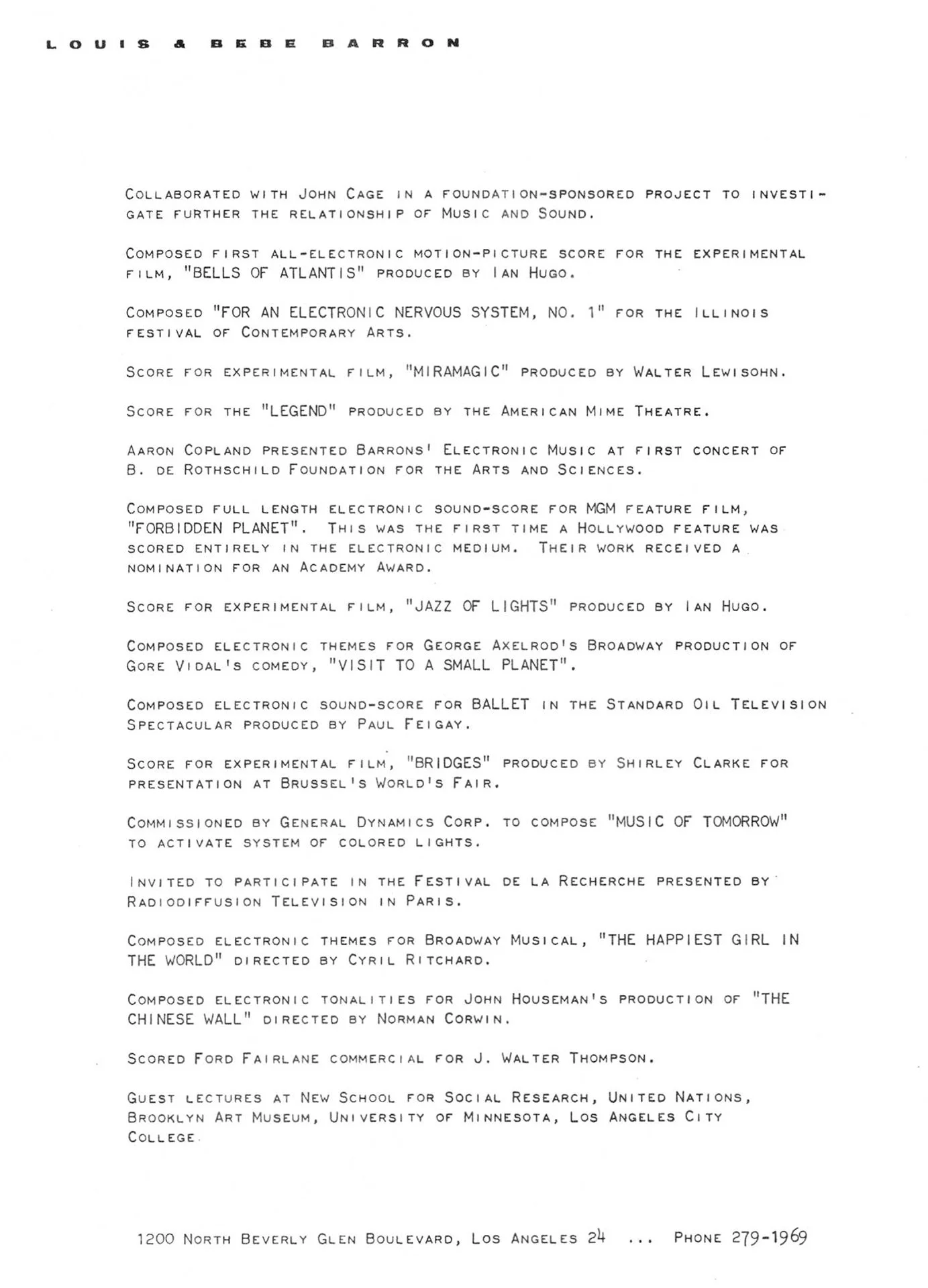

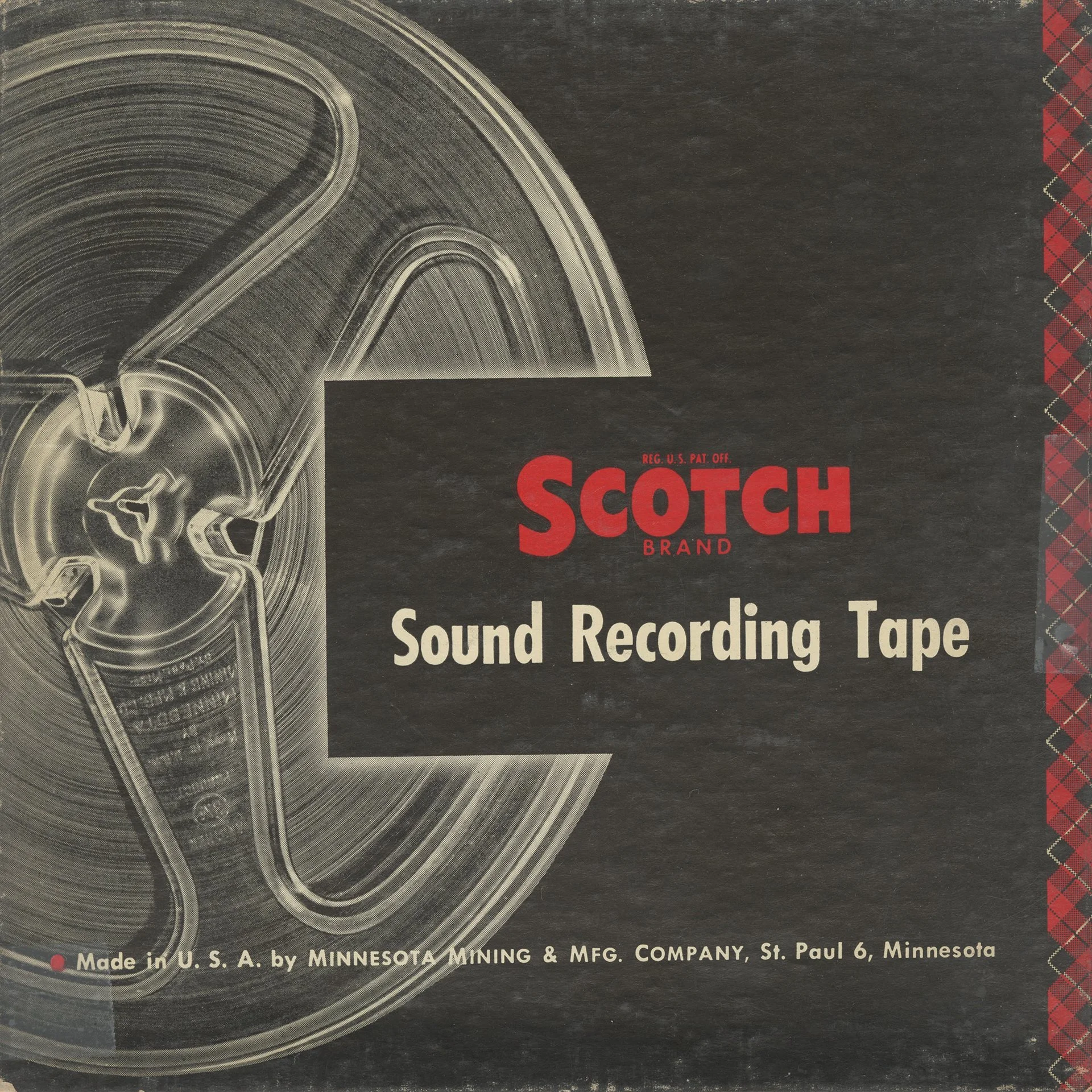

Louis (1920-1989) and Bebe Barron (1925-2008) were pioneers in the field of electro-acoustic music. In the late 1940s, they established one of the earliest electronic music studios in New York and their first experiments with tape technology brought them into contact with the likes of John Cage, Anaïs Nin, Aldous Huxley and many more figures associated with New York’s avant-garde community in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Louis and Bebe became well known to a wider audience for creating the first exclusively electro-acoustic soundtrack for a feature-length film, Forbidden Planet (MGM, 1956). This soundtrack became extraordinarily influential in the development of both electronic music in general, and film scores specifically, for its merging of music and sound effect design. The couple collaborated on work for over 40 years, going on to create many more projects for film and theater, though none are as widely known as Forbidden Planet.

An only child, Bebe Barron was born Charlotte May Wind on June 16, 1925, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Louis Barron, born on April 23, 1920, was a classically trained pianist who eventually found more interest in the early jazz music of the time, was also from Minnesota. While he took some classes at the University of Chicago, he never finished his studies, departing for Mexico and spending time in Cuba to pursue a path in theatrical playwriting. Upon returning to the United States in the late 1940s, he was introduced to Charlotte, who had studied music composition at the University of Minnesota but took a bachelor’s degree in Spanish and a master’s degree in political science. Charlotte was still living in Minneapolis when she met Louis in 1947. They were introduced through Louis’ brother, Jesse, who she was dating at the time, but “wound up with Louis, the more creative, exotic and bohemian” brother, her son Adam said in her obituary for the New York Times in 2008. It was Louis who gave Charlotte the nickname Bebe, which she eventually took as her first name.

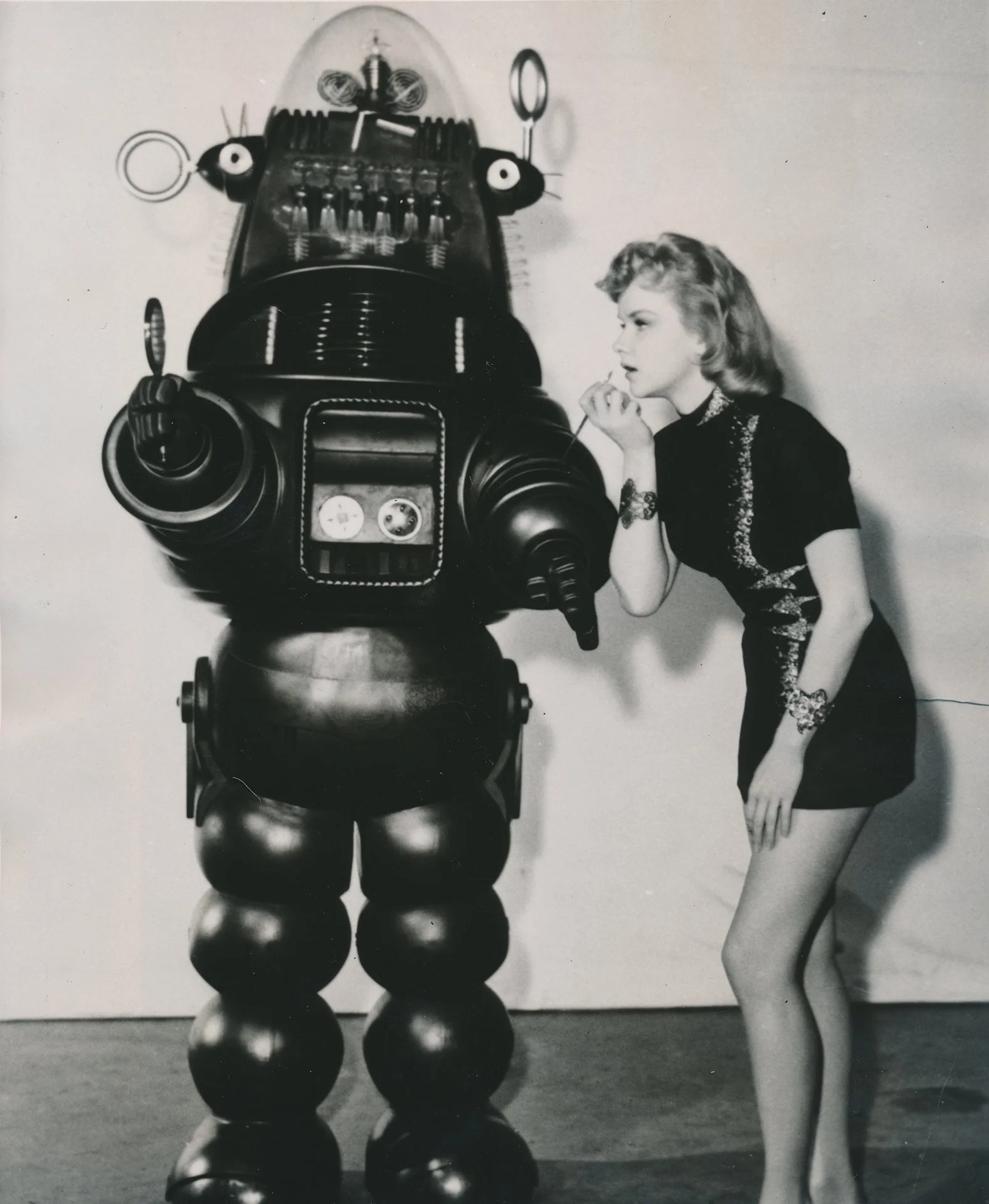

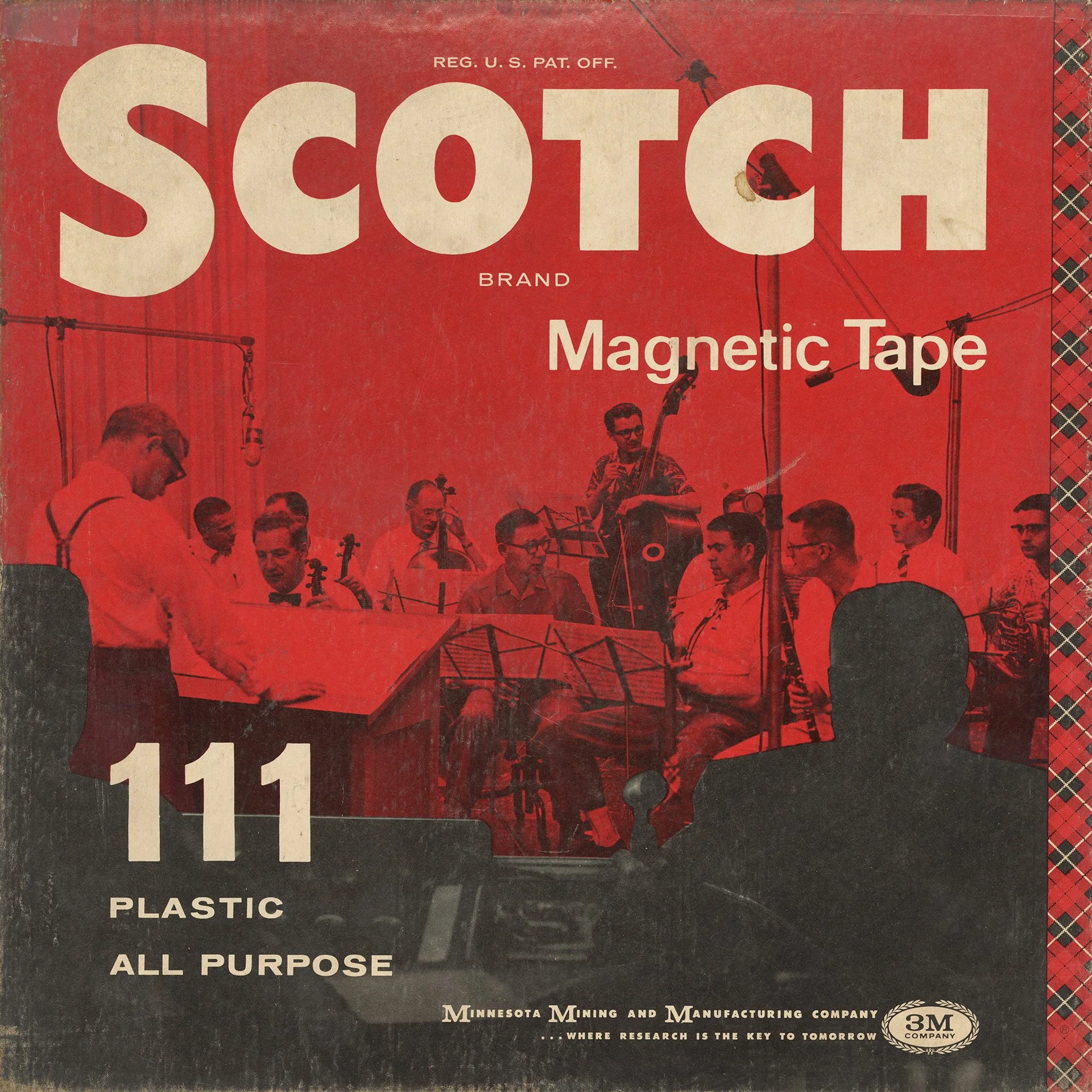

In 1948, Bebe quit her job as a researcher for Time Magazine, the pair got married, and moved to Monterey, California. As the oft told story goes, the couple were gifted an early tape machine from an uncle who was an executive at an audio tape company, 3M. By 1949, the Barrons had moved to New York and set up one of the earliest known private electro-acoustic music studios where they began experimenting with electronically generated sounds. It was at this studio where they embarked on creating early audio books, featuring writer friends such as Anaïs Nin, Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller and Tennessee Williams, a project they titled “Sound Portraits.”

Louis and Bebe Barron were some of the first artists to adopt magnetic tape as a medium of recording, manipulation, and composition for their work. The Barrons’ laborious production process included devising vacuum tube circuitry to create electronic sounds, experimenting with a variety of methods to record these sounds to tape, and eventually curating and editing the captured and manipulated sounds into new musical compositions. It is notable that they were working at the same time - but in parallel to - the likes of Stockhausen as well as the artists behind the movement known as musique concrète. But the Barrons were on their own trajectory and were pioneering a distinctly American form of avant-garde electronic music.

While Louis and Bebe each had musical backgrounds and training, Louis was also a self-taught electronics engineer. And they were both heavily influenced by Norbert Wiener’s 1948 book, Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, which suggested that certain natural laws of behavior apply to both animals and electronic machines. Louis would design vacuum tube circuits based on equations from the book, focusing on designs that were essentially unpredictable. Once activated, the circuit “came to life,” wailing, screeching, or singing until some internal component overloaded and failed. The couple would record the sound to tape, up to and including the circuit’s “death.” As Louis noted in an interview with Keyboard Magazine (1986), “If it sounded good to us, we’d try to capture it on tape. From then on, we’d have the tape as working material.”

But that’s not where their work stopped. Again, from Keyboard Magazine:

“Then I would go through all the tapes and find things I thought had potential for further processing, and were relevant to the film,” Bebe says, explaining the methods used for Forbidden Planet. “Then together we would start processing, and that was the really fun part. The sounds didn’t come out of the circuits sounding the way they did in the end. We did lots of things to those sounds, although we were severely limited by the technology of the ’50s. But we did the usual kinds of things that people did in those days, like tape-speed changes and all. The processing would go on for weeks.” But she points out, it’s not entirely accurate to break down their method into separate stages: “It’s really all one process. After a while, Louis and I got so that we didn’t even have to talk about what we were doing—like playing in a string quartet. We just knew exactly where we were going, and what we wanted to do.”

This kind of dedicated and very precise work led the composer John Cage to hire the couple to record sounds for his piece titled Williams Mix, a 1952 tape-splicing experiment. The project featured more than 600 sounds that were cut into tiny bits of tape and spliced together according to the composer’s score. It took the Barrons more than a year to complete.

Louis and Bebe Barron are most known for composing the first entirely electronic film score for a major motion picture, MGM’s Forbidden Planet in 1956. So far ahead of the curve were they that the release of Forbidden Planet generated a fair amount of controversy during which the team decided to use an unusual credit for their work. As quoted from the journal Cinefatastique (1979):

In the original contractual agreement the credit was to have read “electronic music by Louis and Bebe Barron.” Prior to the film’s release, however, a memo circulated among the MGM executives read: “Do you suppose that perhaps the musicians union will say that they have jurisdiction over this if we call it electronic music?” This new anxiety raised, the Barrons were confronted to renegotiate their contract. Everyone agreed that “electronic music” was a harmless credit, but to be on the safe side they searched for something else, and it was film producer Dore Schary who came up with that great euphemism, “electronic tonalities” to describe their work. Says an exasperated Barron, “It was lawsuit proof!”

What could have been a promising commercial career was later sidetracked for reasons that have become somewhat mythic to those that follow their career to this day. This doesn’t mean that they stopped working; on the contrary they continued their experiments well into the 1970s. The majority of their archive was never released, save for a few smaller independent films and theatrical productions.

But the entirety of their work survives, safely tucked away into a storage facility in California, inaccessible to the public, existing only in its original analog tape format and in hundreds of paper documents. The archive of the Louis and Bebe Barron Electronic Music Studio contains over 500 reels of magnetic tape including master and working tapes, production notes and scripts, correspondence, some of Louis Barron's circuit designs, notes about cybernetics and aesthetics, contracts and business communications, clippings, manuals, and some of the original recording equipment.

Much of the material that makes up the archive has never been released and thus not heard by anyone outside of the artists themselves. This collection was not known to researchers until very recently. Even though the Barron Studio marks an important point in the early history of electro-acoustic music, up to now musicologists and film scholars alike have based their research on interviews and the aural analysis of published soundtracks. The Barron Collection not only contains what are likely the only surviving copies of some twenty productions that Louis and Bebe Barron realized in their studio, but it also provides the sole source material for scores and work notes fundamental for thorough research.

After being introduced to the existence of the archive, Forgotten Futures made an agreement with the Barron Family to digitize the entire audio archive. Forgotten Futures brought on board the renowned audio preservationist, mastering and restoration engineer, Jessica Thompson and soon thereafter, the first transcription tests were underway.

After digitizing about 10% of the tapes, we can confirm that the tapes are in miraculous condition. It gives us very high hopes for capturing the entire archive digitally with minimal need for post capture restoration. While much of the archive is still a mystery, some highlights already uncovered include:

Over a dozen tapes created with John Cage, some of which were working material that led to his Williams Mix, the first known piece presented in octophonic sound;

Early collaborations with Christian Wolff, the experimental composer, and a collaborator of Cage’s;

Several versions and working tapes for projects like Forbidden Planet;

An alternate soundtrack to the submarine film Silent Running which was never used for the film, and the piece Electronic Nervous System - which was eventually cannibalized for use in Forbidden Planet;

Multiple iterations of pieces such as Renata Druks’ Space Boy, demonstrating their compositional process and evolution;

Original recordings with the street jazz musician Moondog;

Soundtrack and working tapes for the films Bells of Atantis and Jazz of Lights; notably both films are currently in the collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The Barron tapes are primarily acetate, dating from the 1950s - 1970s. Though they have been stored well and are in good condition, because of their age and fragility, the tapes need to be handled with extreme care prior to and during digitization. The tapes are being digitized in Broadcast Wave Format (BWF) 24bit/96kHz following guidelines laid out in The Safeguarding of the Audio Heritage: Ethics, Principles and Preservation Strategy. Tapes are played back on an ATR-102 tape machine with analog-to-digital conversion on a Prism Sound Dream AD-2 converter, and simultaneously, as 5.6Mhz DSD. In the absence of tones, standard MRL calibration will be used with azimuth and levels adjusted to program material.

Because these are experimental tape compositions, there may be upwards of 100 splices on a single reel, which is evidence of the Barrons’ curatorial and compositional process. The adhesive on the splicing tape has disintegrated over time, so if the tape is played without remediation, the splices will invariably fail. Therefore, all splices and leader tape are repaired and replaced prior to playback, a time-consuming and laborious, yet crucial part of the preservation process.

During digitization, Jessica Thompson will collect detailed metadata including, at minimum, tape format, speed, and use of noise reduction (if any), work titles or descriptions, additional contributors, content duration, anomalies or audible errors, notable sonic events, and language used to describe the sounds. Thompson will also document the digitization process, including signal path, sample rate and bit depth of digital file, digital file name, location, and MD5 checksum.

Because of the experimental nature of the Barrons’ recordings, at times it is often unclear whether they intended the tape to be played back at 7.5 ips or 15 ips, or, for creative purposes, at both speeds. Playback speed will be determined based on documentation when present or by comparison to similar recorded material. Some tapes may be played back twice, once at each speed, in order to properly preserve the content. Tape boxes and any papers within will be scanned as 600 dpi TIFF files.

The project’s status is ongoing, and we expect it will take years for the painstaking process to be complete. Much of the contents of the archive will not be known until the full archival process has been completed: who knows what mysteries the team will discover along the way.

As Volker Straebel, musicologist and Dean of Music at California Arts University notes, “It is my opinion that the Barron Electronic Music Studio Collection contains material of highest importance for the history of electro-acoustic and avant-garde music in the United States, and it should be preserved and housed at an institution for public access.”

And that is the goal, once the work of digitization is complete. Forgotten Futures, in partnership with the Barron family, will continue to work toward unlocking the Barrons’ work, ensuring that it eventually becomes available for scholarship, research, and entertainment for generations to come.

If you currently have any Louis and Bebe Barron material in your possession, or have a question for the team, please reach out to us at info@forgottenfuturesmusic.org.